Home → Blog → Why Do Strikes Belong to Big Companies? Where Did Restaurant Workers Go?

Why Do Strikes Belong to Big Companies? Where Did Restaurant Workers Go?

A Calgary data story on wages, rent, and why front-line restaurant workers’ rights often stay on paper.

TL;DR · What this story is about

- From 2019–2025, Calgary’s overall average wage grew much faster than wages in Accommodation & Food Services.

- Over the same period, benchmark rent for a one-bed apartment rose by about 25%.

- Restaurant workers are squeezed between slow wage growth and fast-rising housing costs.

- Unlike large, unionized sectors, most restaurant workers have “strike rights on paper only”.

- This post also links to two interactive dashboards on YYC-Wander so you can explore the trends yourself.

1. Wealth, work, and who makes whose life easier

We often say wealthy people “have money”. But money itself is just numbers. What really makes someone wealthy is the ability to buy other people’s time and effort at a low cost.

Someone can drink a hot coffee at 7 a.m. because another person got up at five. Offices are spotless in the morning because someone cleaned lobbies overnight. A family can tap a card for a nice dinner because someone has been standing in the kitchen for twelve hours.

In that sense, the real foundation of wealth is the existence of people who are willing — or forced — to sell their time cheaply. As long as there are enough people ready to work for low pay, the rest of us can save time and keep our lives running smoothly.

2. “Paper rights”: why restaurant workers rarely appear in strike headlines

In Canada, when we hear about strikes, the news usually comes from large sectors: airlines, postal service, transit, teachers, nurses, public servants. These are big systems with big unions and a clear ability to disrupt daily life.

By contrast, when restaurant workers quit, we don’t see breaking news. We simply see a piece of paper taped to the door: “Now hiring. Flexible shifts.”

On paper, many front-line workers have the legal right to strike. In reality, most have no union, no bargaining power, and very little protection. Their “right to strike” exists mainly in the legal text — not in their day-to-day lives.

Poverty becomes quietly institutionalized: low-wage workers are not only constrained by income, but also by how replaceable they are perceived to be.

3. What the wage data says: Calgary’s restaurant pay vs. all industries

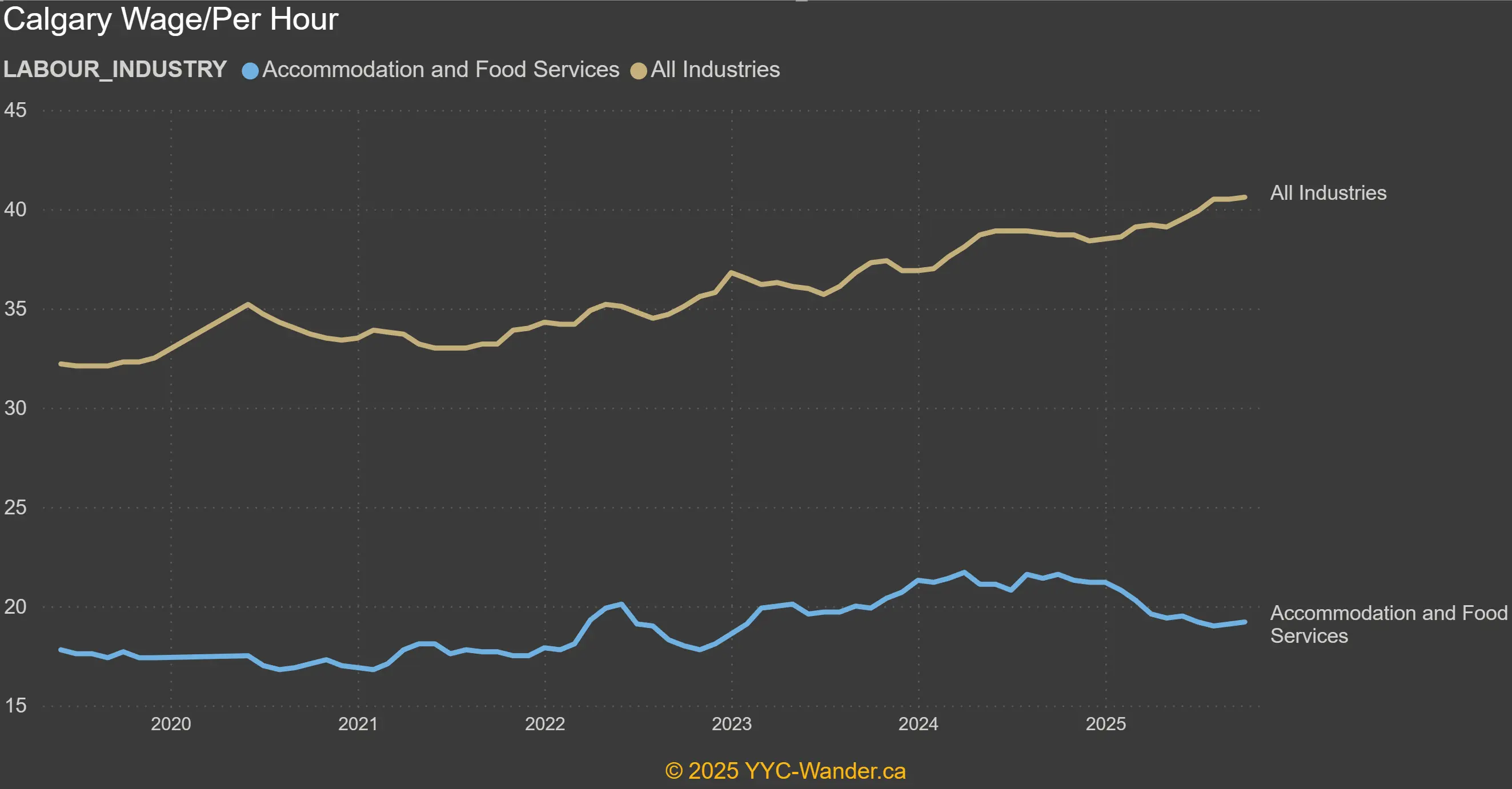

To move beyond intuition, I pulled public data into a dashboard on YYC-Wander: Wage per Hour · by Industry. It tracks average hourly wages in Calgary by industry from 2019 onward.

Two series matter here:

- Accommodation and Food Services (restaurant and hotel workers)

- All Industries (overall city-wide average)

Key points from the data:

- In June 2019, Accommodation & Food Services averaged about $17.80/hour.

- At the same time, the all-industry average was around $32.20/hour.

- By October 2025, restaurant wages had only risen to about $19.20/hour.

- Over the same period, the all-industry average had climbed to about $40.60/hour.

Roughly speaking:

- Restaurant wages rose by about $1.40/hour — an increase of roughly 8%.

- Average wages across all industries rose by more than $8/hour — an increase of around 26%.

Put simply, Calgary’s one-bedroom rents have been rising roughly three times faster than restaurant workers’ wages. The city as a whole became richer, but the people pouring coffee and carrying plates did not keep pace. Their pay moved — just much more slowly than the city around them..

4. Housing costs: when rent climbs faster than restaurant pay

Wages on their own don’t tell the whole story. To understand lived reality, we need to compare earnings with basic costs — especially housing.

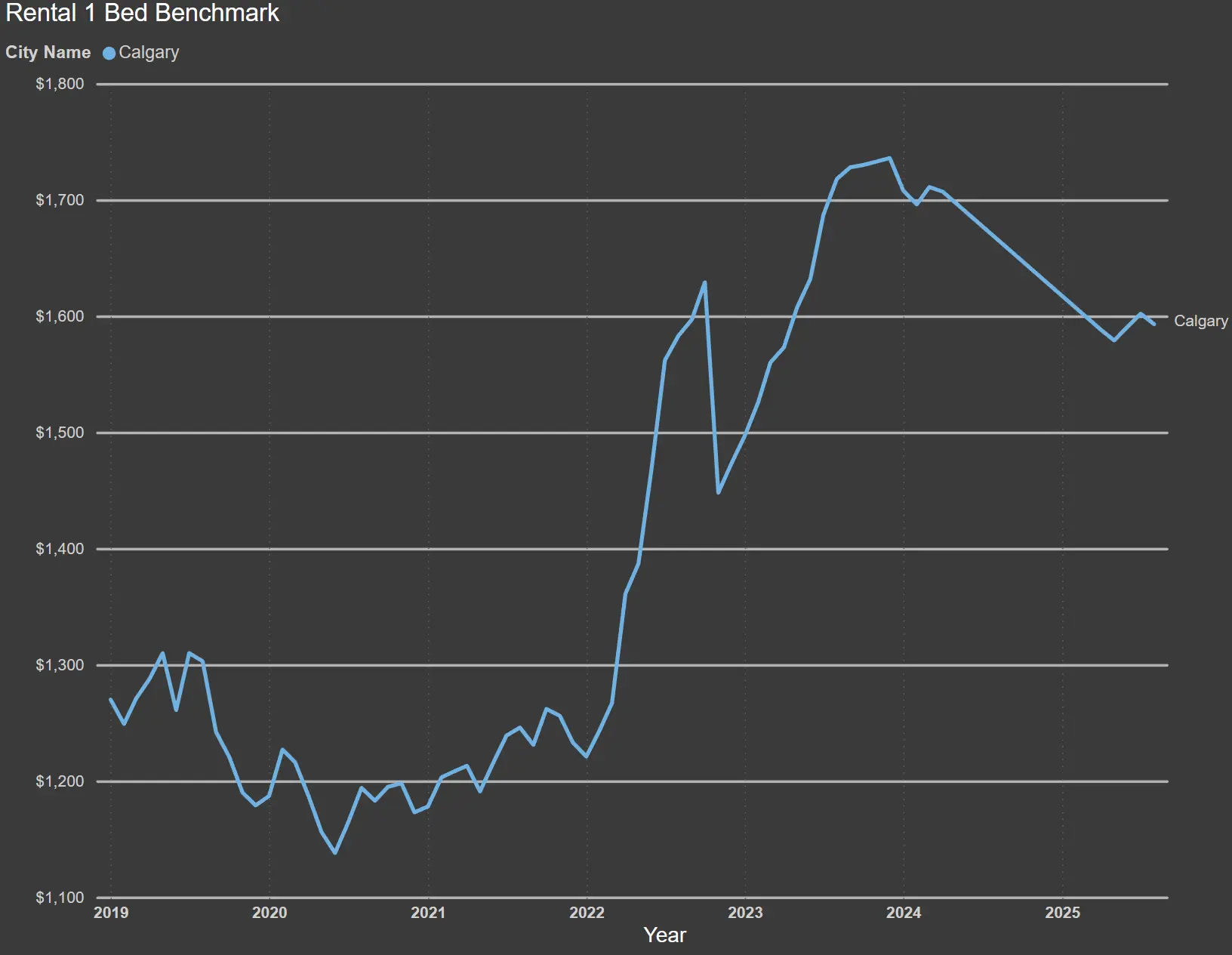

Another dashboard on YYC-Wander tracks the benchmark rent for a one-bedroom unit in Calgary: Rental 1-Bed Benchmark.

From that data:

- In Q1 2019, benchmark rent for a one-bed was about $1,270/month.

- By August 2025, it had climbed to around $1,593/month.

That’s an increase of roughly $323/month, or about 25% over six years.

Put the two trends side by side:

- Restaurant wages: +8%.

- One-bed rent: +25%.

At first glance, that might sound like restaurant wages “kept up a little.” But once we convert hourly pay into monthly income, the gap becomes clear.

Between 2019 and 2025, a full-time restaurant worker’s monthly earnings rose by roughly $224 (from about $2,848 to about $3,072). Over the same period, one-bed rent rose by about $323.

In real terms, that worker is actually about $100 poorer each month than before — even after accounting for the raise. The wage increase doesn’t cover the rent increase, let alone leave room for food, transport, debt, or savings.

Many are not climbing a ladder; they are running in place.

4.5. How many people work in Calgary’s restaurant sector?

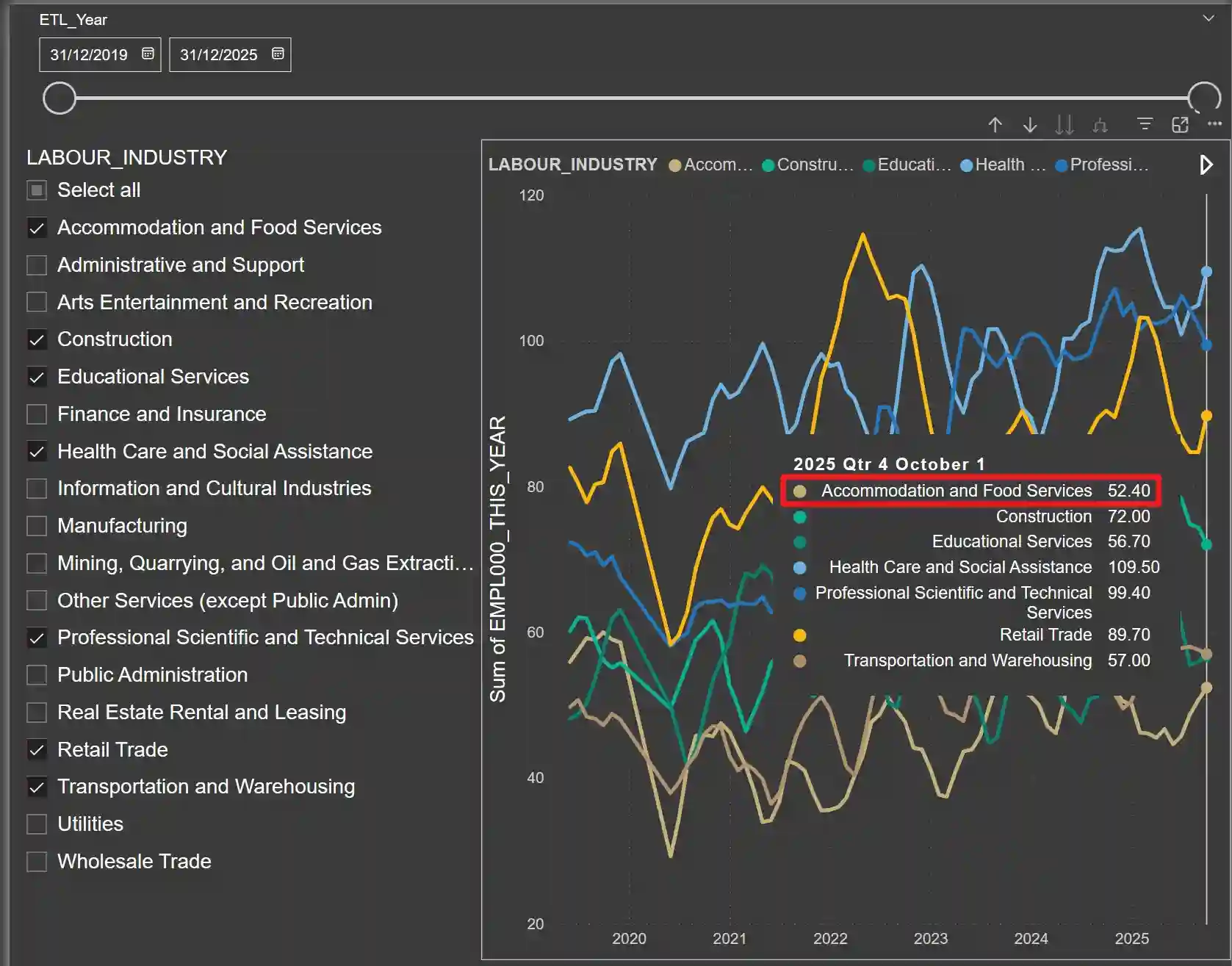

Wages and rents tell part of the story, but scale matters too. In the most recent 2025 quarter, Calgary had about 54,200 people working in Accommodation and Food Services — a large workforce by any measure.

Another dashboard on YYC-Wander tracks how many people work in each industry: Employment by Industry.

For context, recent employment levels look roughly like this:

- Health Care & Social Assistance: ~110k

- Professional & Technical Services: ~99k

- Retail Trade: ~89k

- Construction: ~72k

- Accommodation and Food Services: ~54k

Restaurant work isn’t a small niche. Tens of thousands of people rely on it, yet the sector remains fragmented, high-turnover, and hard to organize. Even though the group is large, their collective leverage stays limited.

This helps explain why slow wage growth in such a major sector has city-wide effects — on housing pressure, household budgets, and how people move through the labour market.

5. Why strikes seem to “belong” to big companies

When a major airline or transit system goes on strike, the entire country feels it. Flights are cancelled, buses stop, packages don’t move, schools close. These sectors have large, organized unions and real leverage over the system.

Restaurant workers, by contrast, face several structural barriers:

- Many are part-time, students, newcomers, or people between jobs.

- Workplaces are small and scattered — thousands of separate employers instead of a handful of big ones.

- Unionization is rare; turnover is high; people leave quietly rather than organizing publicly.

- From an employer’s perspective, there is always another CV coming in tomorrow.

Their legal right to strike hasn’t disappeared, but without organization and leverage, it is effectively a “paper right”. It exists in legislation, not in everyday practice.

6. What would it mean for a city to be truly “warm” and “civilized”?

Canada is often described as balanced, moderate, and kind — and in many ways, that is true. But a comfortable pace can also hide uncomfortable realities:

- Balance is not the same as fairness.

- Warm tone is not the same as everyone feeling warmth.

A truly civilized city is not measured only by how many people become wealthy, but by how it treats the quietest people in the room: the ones washing dishes, wiping floors, and carrying plates.

Do they have any real say over their schedules and pay? Are they able to afford safe housing within commuting distance? Or are they simply treated as infinitely replaceable — a background resource?

Maybe genuine prosperity is not about rich people having ever more choices, but about poor people no longer being so cheap. Data doesn’t give us the moral answer, but it does remind us who absorbs the cost when wages lag far behind rent.

If you found this post useful and want to explore more Calgary-focused dashboards and stories, you can start from the homepage: YYC-Wander · In my journey through the urban landscape.